The (sUAV) small unmanned aerial vehicle – otherwise called a drone – is changing the cost equation for rapid mapping at a fast pace. It is usually not financially viable to mobilize a manned aircraft for a small site-mapping project. A drone-based collection system, on the other hand, can just be another piece of equipment in a surveyor’s truck but, if you must go back and do something over, the cheap option doesn’t represent the total expense you’ll incur. Organizations sometimes choose photos because they are a cheaper option but, if they aren’t experienced enough to pull off what they need, they end up incurring a big expense.

Drones, once the realm of professionals and well-to-do hobbyists, have increasingly become more accessible and costs have dropped substantially over the past few years as we have seen this technology increase exponentially. While early drone designs were more of a backyard novelty, the newest drones are loaded with advanced cameras and stabilization technology that allows for a diverse array of use cases. Whether you’re traversing the bridges of a modern city or hiking a mountain, there are sights worth preserving in a photograph and, while handheld cameras can capture the human viewpoint, drones offer a completely different perspective. With the advent of low-cost drones equipped with high-resolution cameras, taking aerial images is now easily affordable for photographers. Images and video taken from the air offer a perspective that cannot be matched from the ground, and drones can safely operate at much lower altitudes and in more confined spaces than aircraft.

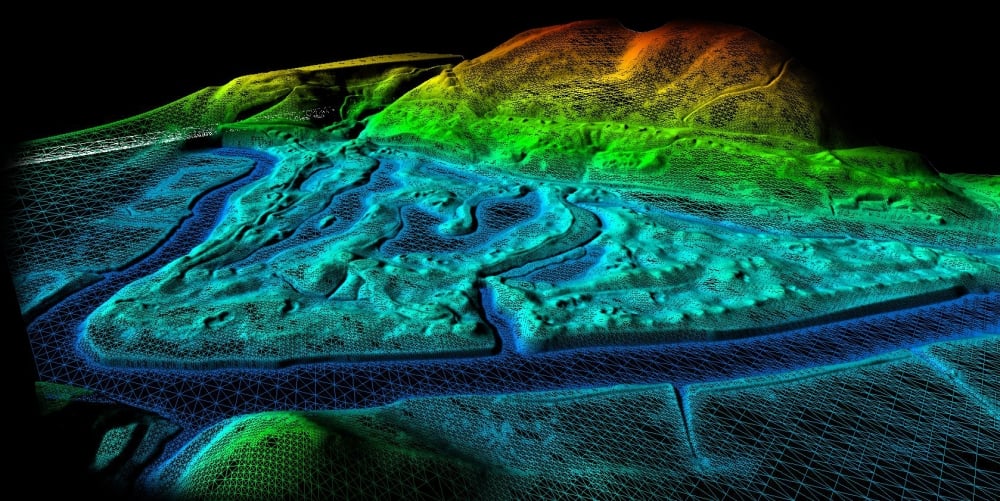

Present day drones introduce dozens of inter-related artificial intelligence aspects that are driving and supporting todays drone economy. They have brought photogrammetry to the forefront in an incredibly powerful way and have enabled much more developed conversations. Rather than convince people a 3D model could be constructed via images, many people have already moved onto asking about the logistics behind the process. Much of that is because people recognize what can be done when the right cameras, sensors, and software are combined with a drone.

The perspective a “drone service” provides is far removed from traditional capture methodologies, as users can control the drone to navigate at certain elevations, get predetermined percentages of overlap, as well as plenty of other aerial angles and views. The volume of data acquisition drones gather allows users to get what is often the perfect image set that will meet many of their needs, which is far different from controlling a human walking around in a space, trying to get sufficient imagery.

The challenge today is that consumers can go to a big box retail store to purchase a drone and connect to a service that provides flight automation and data capture. The result of this purchase flexibility is we end up with people who are asking, “Why this is so hard when there are low-cost solutions that are available and which they can use themselves?” Those are the sorts of people that are running into identified issues and known problems, just because we have so many new people in the space who are not (GIS) geographic information system professionals or surveyors. That’s natural, because it’s what happens when you commoditize technologies – more people can enjoy the benefits, but they’re also going to experience the pains. Experiencing those pains is an issue users and organizations will go through, but sorting out how and why their approach makes sense for a given project needs to be a priority, which ties directly into how they’re using photogrammetry. These enhancements and the general pivot toward drone-based aerial imaging is changing the field of photography and even the photojournalism game as we know it.

Edited by

Erik Linask